The Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery

(c) 2013 Jefferson Davis

Return to main VBMA Cemetery Project webpage

Below is an index of the persons buried at Vancouver Barracks. It was originally researched by Robert and Ruth Crouch around 2002, in cooperation with Mr. Rolf Evans the Mortuary Officer for Vancouver Barracks ( with offices at Fort Lewis, WA.) and Mr. Bob Baerncopf the Sexton at Vancouver Barracks. In 2012, the website constructed by Mr. and Mrs. Crouch dropped off the Internet. We at the VBMA recovered a small part of their original design, and using current cemetery records, reconstructed the entire index and updated it to include burials ending in 2012. All original material (c) Jefferson Davis

A&B, C&D, E&F, G&H, I&J, K&L, M&N, O&P, Q&R, S&T, U&V, W&X, Y&Z

If you are interested in a cemetery walk, please contact us at: President@vbma.us

The Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery hosts ordinary soldiers, general officers, civilians, pioneers, Native Americans, Italian and German Prisoners of War, and most notable, four Medal of Honor recipients. Prior to the establishment of the present cemetery, two older cemeteries existed within the Vancouver Barracks. The original army cemetery, established in the 1850s, and even older Hudson’s Bay Company Cemetery, established by Catholic priests at the Stellamaris Mission.

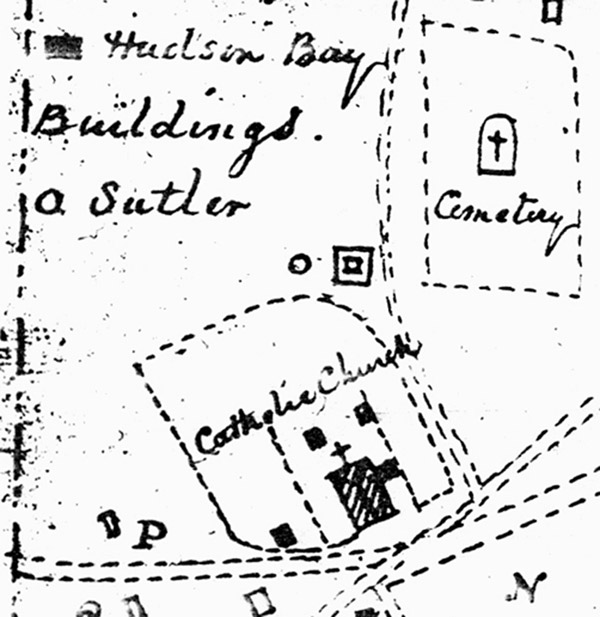

Left,

this portion of an early map of the Vancouver Barracks, showing the

Catholic church and cemetery.

Left,

this portion of an early map of the Vancouver Barracks, showing the

Catholic church and cemetery.

According to surviving records of the Catholic Cemetery, in the years between 1839 and 1856, at least 204 people were buried in the cemetery. Most of them were employees of the Hudson's Bay Company, who came to the area for work. They included French Canadians, Scots, Portugal, Native Hawaiians, (called Kanakans), and Native Americans from as far away as the Iroquois Confederation. In addition to the company employees who traveled to the Northwest, the Catholic missionaries made many converts among local people who either worked for the Hudson's Bay Company, or who visited the mission. They included members of the following tribal groups. Member of the 'Cascades', Chehalis, Chinook, Grande Dalles, Kalapuya, Klickitat, Metis, Pend O'Reille, Quinault, Rogue, Shasta, Snohomish, Spokane, Tillamook, Umpqua, Walla Walla, and Wasco Indian Tribes came to be buried at the cemetery.

This cemetery was established and consecrated by Catholic priests, so normally everyone buried there should have been Catholic. However, it was the only Christian cemetery of any denomination in the region, so they must have made allowances. One internment record stated the dead child of child of Protestant parents was buried there, as was Baptiste, the son of Abraham Rabbi. Even after the United States Army arrived late in 1849, several soldiers and their dependents who may have been Catholic were also buried in the cemetery. According to the records available, the last burial in the cemetery took place on 16 January 1956.

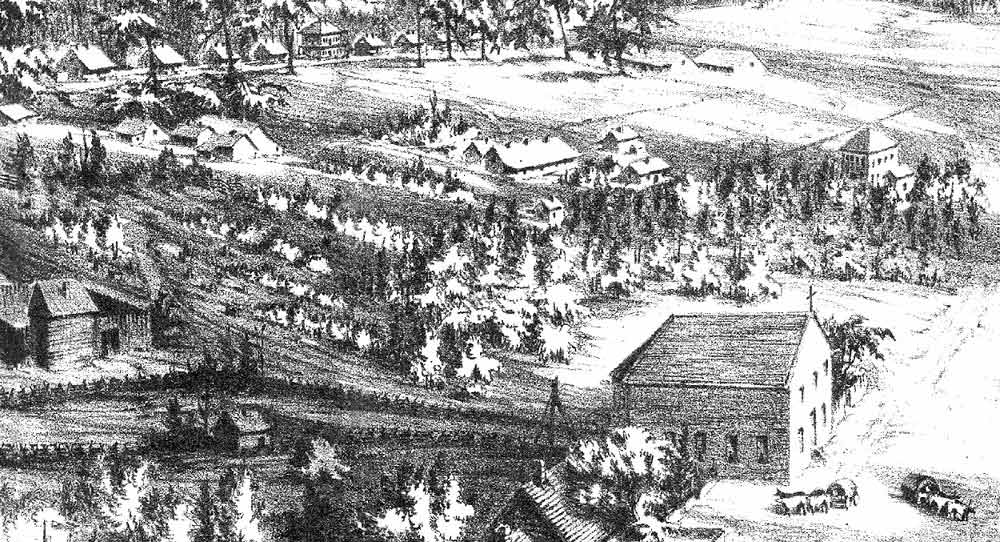

Below, a portion of the 1855 engraving of Fort Vancouver and the U.S. Army Barracks shows the Catholic mission and cemetery. Some of the gravestones are visible in the engraving. Up the slope, the Grant House is clearly visible.

Unfortunately, Good relations did not last between the Hudson's Bay Company, the Catholic missionaries and the United States Army. Although some of the soldiers were Catholic, most were not. Furthermore, when the Hudson's Bay Company moved their operations to Canada in the 1860s, the Catholic priests remained and filed a Donation Land Claim whose boundaries included most of the west end of the US Army post. This was not resolved until the 1880s. In the mean time, the priests wrote of harassment on the part of the U. S. Army. Which may have been why the army established their own cemetery in the 1850s.

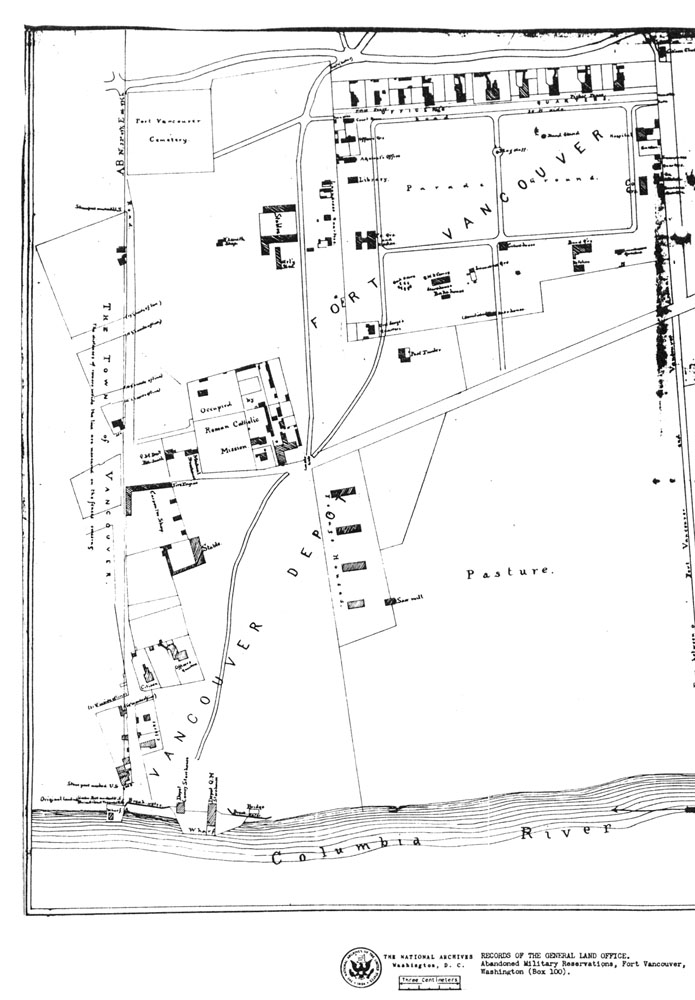

Above, a map of the Vancouver Barracks from the 1870s shows the Catholic mission at the lower left portion of the map but no cemetery. By that time, it had been abandoned. however, in the northwest corner of the map, the cemetery the U.S. Army established in the 1850s is depicted.

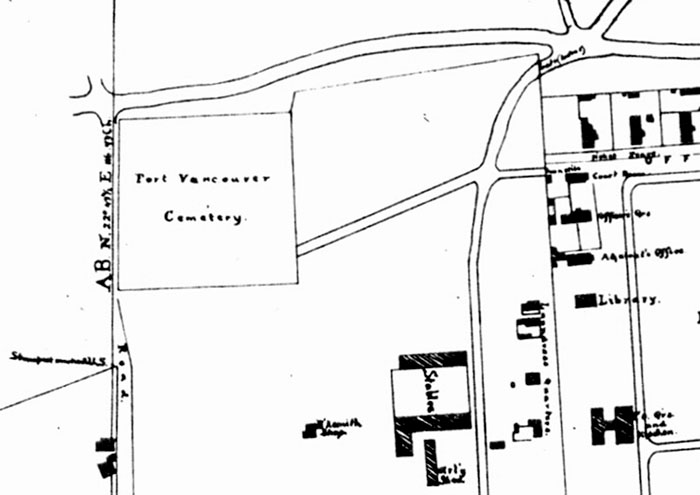

Below is a close up of the first U.S. Army cemetery. Modern day Evergreen Blvd and portions of Officer's Row exist on or near this cemetery.

In the early 1880s, the War Department approved many changes in the buildings and infrastructure at the Vancouver Barracks. To make space for the new buildings, military planners needed the land used by the two original cemeteries. Unfortunately, many of the early markers at both the Catholic and army cemeteries were wood. Most of the wooden markers had decayed to the point of being illegible or had disappeared entirely. Though family members and government contractors moved as many bodies as they could, inevitably them missed many. There are over 1500 graves at the current Vancouver Barracks Post Cemetery, of which 210 are inscribed simply, 'Unknown'.

According to the National Archive Document No. 351000:

“The original post cemetery was in the northwest corner of the reserve, area 4 acres, enclosed by a strong picket fence. Total internments to 12 August 1882 was 314. Of these the number of officers, as far as was known was six; number of enlisted men whose record could be obtained 30; the remainder civilians or person whose graves were without headboards or any other marks to designate who they were. Civilians we encouraged to reclaim and remove the remains of their relatives, about 72 disinterments of civilians occurred during the year 1881. The new cemetery, situated about ˝ mile north of the old one, area 2 acres, was enclosed with a strong new picket fence. No new internments had been made to 12 August 1882. There was some dissention (local) to the disturbance of the burials for reinterment in the new cemetery. Rather it was recommended that the old post cemetery be declared a national cemetery as been formerly done by GO#4 of 1875 subsequently revoked by GO of 1876. The original post was needed for expansion of the building area of the Reservation.

Notable Burials within the Cemetery

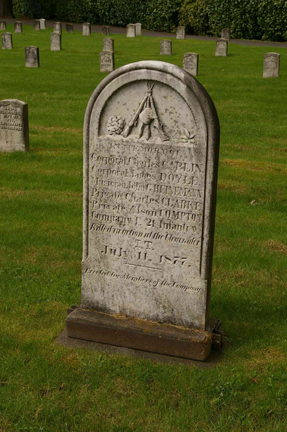

John Heinemann, army musician wrote a letter to his family in 1876. It was the last they heard of him. Heinemann and several other soldiers, most of whom were musicians died with him at the battle of Clearwater, in the Idaho Territory. A marker was raised for them at the Vancouver Barracks.

Some burials definitely predate the current cemetery, like Rolla, an ‘Indian Boy’ who died in 1860.

A few graves belong to people who traveled longer distances. Sergeant Thomas Laws was died in the Philippines and his body traveled back to the United States for burial. Probably the largest number of graves come from World War II. Although many of the burials date to the war, service members who died at the Barracks, a small number of people buried at the Vancouver Barracks were not Americans. During the war, several thousand Italian and German soldiers were interred in the northwest. Most survived the war, and returned home. A handful died before that could happen, and were buried among their former enemies, equal in death.

The Medal of Honor

"The Medal of Honor is oftentimes called the Congressional Medal of Honor, because it is presented to soldiers by the President of the United States on behalf of Congress. It the highest award bestowed by the Army: to a person who, while a member of the Army, distinguishes himself or herself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his or her life above and beyond the call of duty while engaged in action against an enemy of the United States; while engaged in military operations involving conflict with an opposing foreign force; or while serving with friendly foreign forces engaged in an armed conflict against an opposing armed force in which the United States is not a belligerent party. The deed performed must have been one of personal bravery or self-sacrifice so conspicuous as to clearly distinguish the individual above his or her comrades and must have involved risk of life... "

"[It began]…after the Revolutionary War. Decorations, as such, were still too closely related to European royalty to be of concern to the American people. However, the fierce fighting and deeds of valor during the Civil War brought into focus the realization that such valor must be recognized. [The U.S. Senate] provided that: "The President of the United States be, and he is hereby, authorized to cause two thousand "medals of honor" to be prepared with suitable emblematic devices, and to direct that the same be presented, in the name of Congress, to such noncommissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldier-like qualities during the present insurrection…”

Department of the Army

Institute of Heraldry

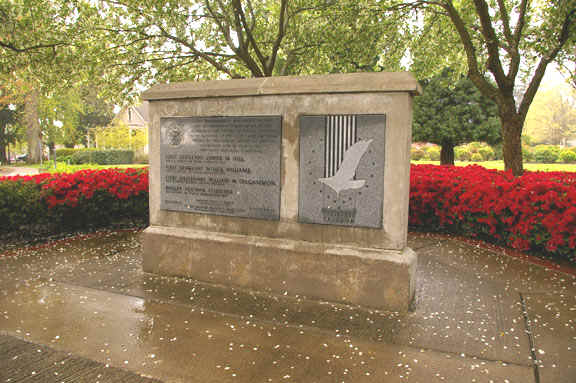

The four Medal of Honor recipients buried at the Post Cemetery are Sergeant James Madison Hill, Major William McCammon,

Private Herman Pfisterer, and First Sergeant Moses Williams.

The monument pictured above was dedicated to them in 1991 by (then) Secretary of State Colin Powell

James Madison Hill

During the Arizona Indian Campaign of 1873, First Sergeant James Madison Hill served with Company A, 5th U.S. Cavalry. His unit engaged the enemy at Turret Mountain, in Arizona on 25 March 1875. His medal citation simply says, “Gallantry in action,” leaving the reader to wonder what else was going on. Hill stayed in the Army, and became the Commissary Sergeant at Vancouver until he retired in 1899. He died in Vancouver on Sept. 17, 1919 of “arterio sclerosis.”

William Wallace McCammon

In the Civil War, First Lieutenant William McCammon was a member of Company E. of the 24th Missouri Infantry. On October 3, 1862, his unit engaged Confederate forces near Corinth, Mississippi. And, “While on duty as provost marshal, voluntary assumed command of his company, then under fire, and so continued in command until the repulse and retreat of the enemy on the following day, the loss to the company during the battle being very great.” McCammon continued in the Army, eventually coming to the Vancouver Barracks. At one point, he was temporary commander of the Vancouver Barracks, but his normal position was commander of Company D, of the 14th Infantry.

Herman Pfisterer

Courage can come to anyone, when they need it, even to musicians. Private Herman Pfisterer came a long way from his native Brooklyn to become the bugler for Company H., 21st U.S. Infantry, during the Spanish American War in Cuba, in 1898. On 1 July of that year, his unit was heavily engaged in an attack at Santiago, Cuba, and suffered heavy losses. Private Pfisterer “Gallantly assisted in the rescue of the wounded from in front of the lines and under heavy fire from the enemy.” Later Pfisterer served as a bugler with the Company D, 14th U.S. Infantry at Vancouver Barracks.

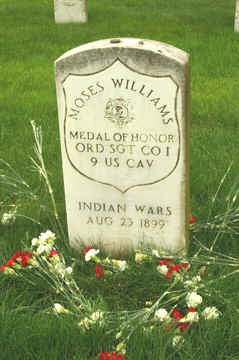

Moses Williams

First Sergeant Moses Williams was a “Buffalo” soldier, serving in Company I, 9th U.S. Cavalry during the Apache War in 1881, a unit made up primarily of African American troops. On 16 August 1881, while on patrol near the Cuchillo Negro Mountains of New Mexico, the Apache attacked. First Sergeant Williams: “Rallied a detachment, skillfully conducted a running fight of 3 or 4 hours, and by his coolness, bravery, and unflinching devotion to duty in standing by his commanding officer in an exposed position under heavy fire from a large party of Indians saved the lives of at least 3 of his comrades.” Williams remained in the Army, and became the Ordinance Sergeant at Fort Stevens, delivering supplies to various Coastal Artillery Batteries along the Washington and Oregon Coasts. When he retired in 1899, Williams moved to Vancouver, and died in bed of heart failure, three weeks later.